Roger & Me

Steganography & Roger Craig's Getaway Car — An Appended, Illustrated Post of My 1995 Essay

“I was … motivated by a civic duty to report a suspicious automobile, which I spotted in 1989 … fitting the description of a getaway car seen by several JFK assassination witnesses leaving Dealey Plaza in my hometown of Dallas. My police chief, Jesse Curry, went on TV the week of the assassination and asked all citizens to report anything suspicious. So I did … 30 years later.”1

Belief & Knowledge

To paraphrase the opening of Jim Marrs’ book, Crossfire: the Plot that Killed Kennedy, don’t trust this article. In fact, when it comes to the assassination of President Kennedy, don’t trust any one source or even the basic evidence and testimony. Belief and trust are part of the problem. Just because we believe there is a conspiracy, that doesn’t mean there is one. And just because we don’t believe in conspiracies, that doesn’t mean they don’t exist.

There are those who say belief in conspiracy is at best irresponsible, and at worst insane (or paranoid, a word they may misuse to mean the same thing). There are those who say believing Oswald acted alone is at best naive, and at worst criminally insane (or part of the cover-up, which may mean the same thing).

The first thing we can be certain of is that one of those two beliefs (conspiracy or no conspiracy) is the truth. The assassination did happen. It happened only one way [quantum physics aside] and it happened that way only once. The second thing we can be certain of is that some of those who are telling us these things as fact are Iying. They are Iying to us, and they are Iying about us. Some of these liars are our teachers; some of them are our bosses; some of them are our city council representatives; some of them are our House and Senate representatives; and some of them are our country’s vice presidents and presidents. Every day for 30-plus years, these liars have been making decisions that affect us.2

For Hitler and the Nazis, lying was a matter of policy. They knew that if they lied often enough, a certain percentage of their lies would be believed. And if one big lie were told often enough, much of the population would eventually come to believe it. That was the Nazi theory of propaganda — a theory I might add, very familiar to two members of the Warren Commission: Allen Dulles and John J. McCloy. So we have to know who the liars are. The only way to do that is to judge them by the facts — not the other way around.3

Aside from knowing who is Iying to us, why should we care about who killed the 35th president of our country? The answer to that question is the same as the reason we should care about history. That reason was expressed well by David McCullough, author of the recent best-selling biography of Harry S. Truman. In a speech he gave at the National Archives in 1993. The reason we should care, he said, is because,

Always, always, one thing leads to another. That is fundamentally, irrevocably, one of the most obvious and most important lessons of history. One thing leads to another. It is why it is so important to understand the chronology of events, or the chronology of a life.

It’s also true as a lesson of history that nothing happens in a vacuum — nothing. Nor does anything have to have happened the way it happened. We are often taught history in such a fashion as if everything happened on a track from the moment events began until the present day. And never ever was that so.

Events, individual lives, the course of national destiny can go off in any number of directions at any point along the way, and for all kinds of unexpected and surprising reasons. The people who are involved in the event at the time don’t know how it’s going to come out anymore than we do right now.4

McCullough went on to say, “We cannot have the arrogance of looking down on them because they didn’t know how it was going to come out or because they didn’t know what we know now.”

But, as important as it is to know these things, when it comes to the assassination of President Kennedy — believe what we might — as a country, we don’t know the chronology of events. We don’t know which events and individuals, or even whether events and individuals significantly changed the course of our national destiny. We don’t know what the unexpected and surprising reasons are. As a country, we know no more now than we did in 1963. It was sometime in the eighties that history books started to reflect this uncertainty, repeating the Warren Commission findings while at the same time calling Oswald the alleged lone assassin. It was just a couple of years ago that the respected Pelican History of the United States began saying that Kennedy was killed as the result of a conspiracy. If nothing else, the debate that began with the filming of Oliver Stone’s JFK, and which continues today, reveals the country’s historical dilemma.

Study & Action

Six years, five months, and over a hundred books ago, I asked myself a question. How much is it possible to learn about the assassination of John F. Kennedy? The 25th anniversary was looming and I knew from past experience, having been interested in the mystery since that day in Dallas, there would be the inevitable barrage of information, misinformation, and disinformation from the advertising-entertainment-news media. This time, I was determined to put what I would hear and see in the next nine weeks into one of those three categories.

I started reading and re-reading everything I could. My only rule was to read something every day about the assassination. The 25th anniversary came and went, and the only thing I knew for sure was that, despite my casual study of the case for most of those years, I still had misconceptions about it, and I still had huge gaps in my knowledge of it.

In the past, I had always been able to develop informed opinions about the things I studied: art, dinosaurs, plate tectonics, extraterrestnal life, whether or not to wear a seat belt, or whatever. In some cases, after studying a subject, when my personal opinion was not the accepted view, it eventually became so. In those instances, I felt I had developed what Ernest Hemingway called, “a built-in, shockproof crap detector.”5 It made me confident enough in my ability to educate myself (which is the goal of a formal education) to attempt to develop an opinion about the Kennedy assassination. One with which I could feel secure. I stuck to my rule and read something about it every day.

After the first few books, I became more confused. After ten books, I began to get a feel for the subject. A learning curve had started to kick in. The more I learned, the more I was able to learn. I started catching authors in mistakes and, in a few cases, outright lies. I learned that, though there are disagreements about specific details, there are facts (usually ignored by the media) which are undisputed among honest students of both the assassination and the two major federal investigations of it. I learned that — despite all the loose talk about theories — among the honest students whose works I’ve read, there are no theores in the derogatory sense — only a determined effort to account for the facts by considering all of the evidence.

As I was learning these facts, I increasingly felt the need to do something other than read — I was learning that knowledge compels action. But I knew that I was not yet knowledgeable enough to start investigating the loose ends myself. I thought, at most, I would resolve my own personal questions about the assassination and watch events develop from an informed perspective. Two years went by before I contacted another researcher and offered to help. But before that — nine months into my daily reading program — something happened that eventually took me beyond both reading and assisting in research. I didn’t know it at the time, but I had stumbled upon potential new evidence in the case.

Insignificance & Relevance

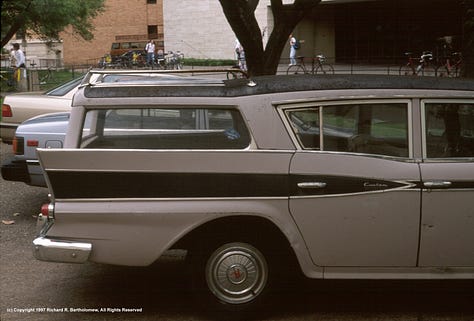

By May 1989, I was familiar enough with the story of a getaway car seen in Dealey Plaza (a story that was dismissed by the Warren Commission) to take more than a passing glance at an old Rambler station wagon parked on the UT campus among the late model Hondas and Toyotas.

It was anachronistic. But it interested me because it was the same make and model as the getaway car I had been reading about. I wasn’t crazy enough to think it was actually that car. I was just glad to have a mental picture of a Rambler station wagon from that era. I had never really seen one. There were, however, some strange things about it that made me wonder whether or not its owner also knew the story about the Dealey Plaza getaway car and its role in the assassination.

Ten minutes after President Kennedy was shot, Marvin Robinson, Helen Forrest, and Dallas Deputy Sheriff Roger Craig, independently of each other, reportedly saw two men leaving Dealey Plaza in a light-colored Rambler station wagon. One of them entered the car on Elm Street after running from the direction of the Texas School Book Depository (TSBD). Craig and Forrest described this man as being identical to Lee Harvey Oswald. A few minutes before this incident, Richard Randolph Carr saw two of three men, who had come from behind the TSBD, enter what was apparently the same Rambler parked next to the building on Houston Street. He saw the third man enter the car seconds later on Record Street, one block east, and two blocks south of the TSBD.6

The Warren Commission had Marvin Robinson’s and Roger Craig’s reports of November 23, 1963. lt also had Craig’s statement to the FBI from the day before, as well as Carr’s statements to the FBI and Craig’s testimony. The Commission, however, apparently never knew about Mrs. Forrest, and did not publish Robinson’s statement.7 It chose not to believe that Craig took part in Oswald’s interrogation or that Craig identified Oswald as the man who entered the station wagon. Dallas Police Captian Wiil Fritz, Oswald’s interrogator, denied to the Commission that Craig was present. Fritz thus never had to deal with Craig’s allegation that Oswald admitted to Fritz that he had indeed left Dealey Plaza in a station wagon belonging to a woman named Mrs. Paine.8

Despite the Marvin Robinson statement that corroborated Roger Craig and which the Commission had, and despite other corroborating evidence such as newspaper photographs showing Craig’s presence on Elm Street, and FBI reports of him in the interrogation room with Fritz during Oswald’s questioning. The Commission chose to believe the contradictory and unsupported testmony of taxi driver William Whaley.9 Whaley told the Warren Commission about two witnesses who saw Oswald enter his cab. But there is no indication that the Commission ever attempted to locate, through the simple process of examining the cab company’s records, the only two people who could corroborate Whaley.”10

With the Warren Commission’s attempt to hide Marvin Robsnson’s statement, the death of William Whaley in 1965, and the 1975 death of Roger Craig after his many failed attempts to make his story public, the truth about this alleged getaway car has eluded the few who have tried to seek it.11

The House Select Committee on Assassinations (House Committee) apparently attempted but failed. It reported, “Robinson did not testify before the Warren Commission, and he has not been located by the committee.” Despite this attempt, however, the House Committee, like the Warren Commission, avoided the entire matter in its report, choosing instead to repeat the Commission’s conclusion that “shortly after the assassination, Oswald boarded a bus, but when the bus got caught in a traffic jam, he disembarked and took a taxicab to his rooming house.” In this, as in many other areas of its investigation, the House Committee had it both ways by concluding that “The Warren Commission failed to investigate adequately the possibility of a conspiracy to assassinate the President.” Thus leading to the conclusion — voiced in 1980 by authors DeLloyd J. Guth and David R. Wrone — “after careful study of the House Committee Final Report, that this most recent official version does not satisfy the need for a thorough inquiry into what happened that day in Dallas.”12

Hypothetically, if the getaway car continued to exist for the past 30 years, given the muddied trails, suspicious deaths, and failed investigations, any persons who secretly knew of the car’s role in the assassination and also knew that it still existed, could safely assume it would never be identified. If one such person decided to reveal the car’s secrets, however, how would he do it? Could he do it without being silenced himself? Could he do it in a way that would survive his own death?

Steganograghy & Detection

It was six years ago, on May 29, 1989, that I saw the Rambler station wagon on the campus of the University of Texas at Austin (UT) which fit the description of this getaway car reportedly seen by Craig, Robinson, Forrest, and Carr on November 22, 1963."13 A cursory examination of the car has revealed apparent associations between it and persons whose lives were intertwined with Lyndon Johnson’s political machinery, the military-industrial-intelligence complex in the U.S., right-wing politics, and Latin American politics.

Connections between odd characteristics of the car itsef and information found elsewhere on the UT campus could be interpreted as a trail of clues in the form of coded messages14 connecting this Rambler, its owner at the time, and its previous owner to the JFK assassination. These clues appear to have been deliberately planted due to specific interrelationships in their content and the encoding technique used. They were in the form of specific pages torn out of UT library books on the assassination related topics. Finding them was a direct result of my daily reading program. It started in the summer of 1989 when I discovered the mutilation of UT’s only library copy of Anthony Summers’ 1980 book, Conspiracy. I was determined to find what was written on those missing pages. What I discovered in those and in missing pages in other books were stories about people not only connected to each other and to Lee Harvey Oswald but, as I came to discover, to the strange things about the UT Rambler, and to individuals at the University of Texas itself.

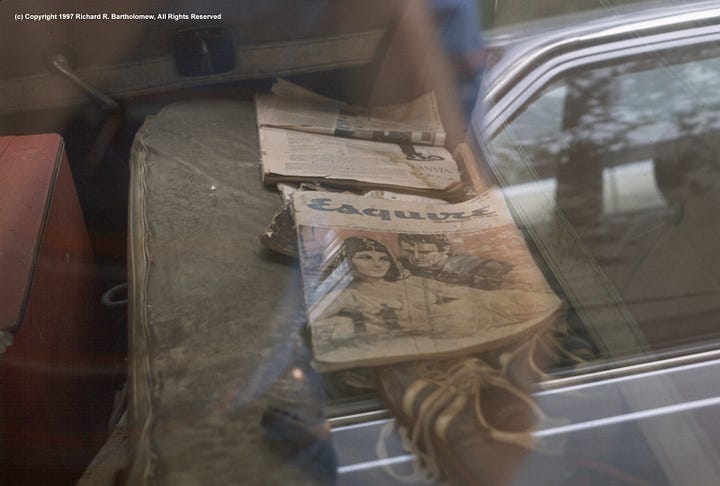

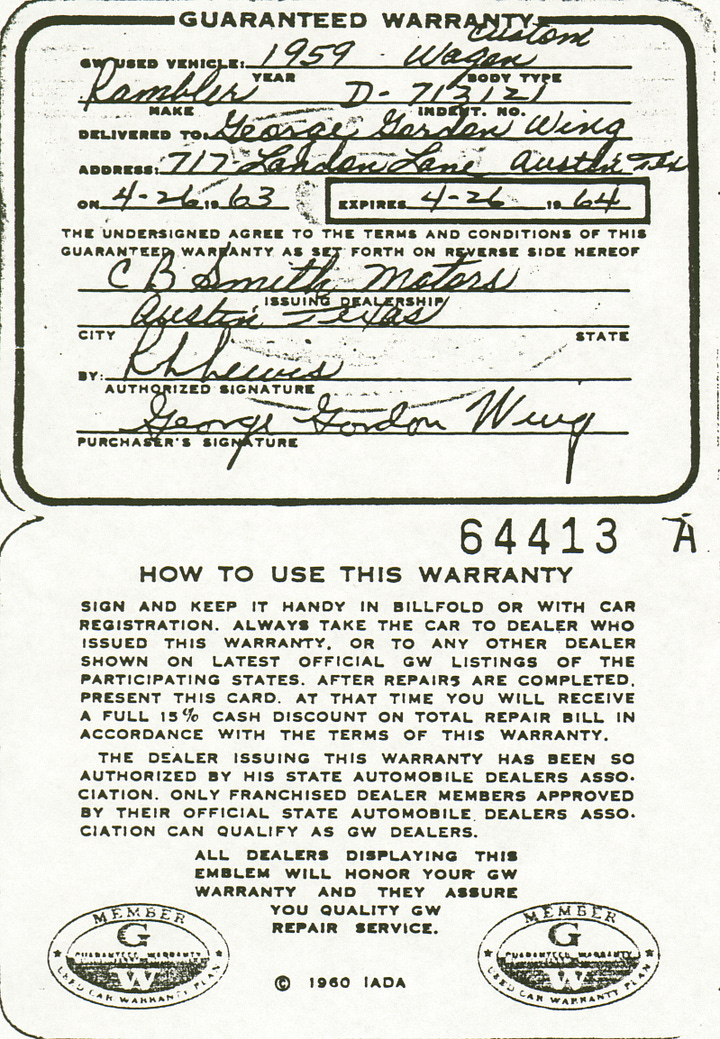

The Rambler was found bearing a 1964 Mexico Federal Turista window sticker and displaying at least two magazines published in 1963 on its rear seat. They remained in that location unmoved and untouched for at least two years. The car was owned by a Spanish professor, which he bought from a very close friend of Lyndon Johnson in April 1963. The used car lot’s sales manager who signed the car’s warranty died of a heart attack after feeling a sharp pain in his back while sitting in a dark movie theater. He died only seven weeks after the assassination. Although all of this made it only a minor curiosity, it became increasingly intriguing with subsequent study.

Physical, anecdotal, and documentary evidence has revealed a mosaic of relationships extending from the car’s owners to individuals who have been, and are currently subjects of interest to researchers of the conspiratorial aspects of the assassination of President Kennedy.15 As researcher Dennis Ford wrote in the November 1992 issue of The Third Decade, the leading journal of Kennedy assassination research, “Discovering the fate of the Rambler will go a long way toward solving this case.... Whoever took or drove the car that afternoon was obviously a conspirator.”16

In 1993, I wrote about all of this in a research paper that reports on my findings and proposes a more in-depth investigation. In June 1993, I presented the paper at a regional conference on Kennedy assassination research. It was well received. Dennis Ford called it a potential breakthrough. In the paper, I argue that the UT Rambler represents a possible unique opportunity to determine the fate of this alleged getaway car by investigating new leads, current clues, and fresh trails: an opportunity that should not be overlooked. I also named lots of names, including local people both living and dead; people with current and past involvement in the administration, and faculty of the University of Texas at Austin. While I have no intention of implicating innocent people in the assassination of President Kennedy, these names cannot be avoided. They are an intimate part of these circumstances that compel further investigation.17 In writing this paper I presumed, as advised by the United States Constitution, that every person referred to therein is innocent. But I also presumed that, as advised by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, “The more outre ́ and grotesque an incident is, the more carefully it deserves to be examined....”18

Skepticism & Denial

Many researchers of the JFK assassination eventually pass a difficult psychological threshold. When confronted with the first evidence of conspiracy, most rational people have no doubt responded, “So what?” The circumstantial evidence I write about is far from immune from such skepticism. The threshold is different for each person because it is defined by individual tolerance for the number of times they can say “so what” before skepticism becomes denial. Denial is perfectly understandable because the alternative leads to frightening speculation about the meaning of events in the recent history of the United States.

One of the researchers who made some of these discoveries has been valuable in the role of the devil’s advocate. His arguments become circular, however, when he insists that because no hard evidence has been found, none should be sought. “Pursue the UT connections,” he said, “and leave George Wing and his Rambler out of it.” But if nothing else, the evidence presented here, stemming directly from Wing’s outré and grotesque station wagon, is a map possibly leading to several “smoking guns.”

I’ve made a sincere effort to avoid direct claims of involvement by the individuals named in any conspiracy to assassinate President Kennedy. The implications, however, are unavoidable. Taken in the context of the research of others over the past thirty years, this evidence can be viewed as part of a substantive circumstanual case that begins to define the conspiracy.

If the UT Rambler was used by the conspirators in the JFK assassination, then it was in Mexico in 1964, ended up back in the United States as some sort of souvenir, and stayed near a circle of friends that included Lyndon Johnson, his close advisor Walt Rostow, UT adjunct professor Jack Dulles, former UT president and chancellor Harry Ransom, Lyndon Johnson’s friend, C.B. Smith, and two professors of Spanish and Portuguese at the University of Texas at Austin.

According to the rule of falsifiability, if this car was not involved in the assassination, the evidence will prove the claim (that it was involved) false. If the claim is true, the evidence will not disprove it. So far, none of the evidence disproves that this station wagon was the car seen by Roger Craig, Marvin Robinson, Helen Forrest, Richard Carr, and others.19

Neither does it disprove the Rambler was the one known to Oswald as the car that took him from Dealey Plaza. On the contrary, in the last year, information about the car’s longest owner, the late Dr. George Gordon Wing, has revealed astonishing potential links between him and CIA veterans such as E. Howard Hunt, Tom Braden, and Cord Meyer. Those men, in turn, have strong links to either the assassination or to the Oswalds’ mysterous friends Ruth and Michael Paine. Wing received a student grant while studying in Mexico City in 1950. That money appears to have come from a known CIA conduit helping to recruit anti-communists to infiltrate Mexico’s student organizations. The search for evidence continues. Help in that search is now coming from many individuals.

Tragedy & Hope

Perhaps this partcular car had nothing to do with the assassination. Perhaps like the back seat magazines and the missing pages, it too was just a sign or a signal, something that would attract the attention of someone knowledgeable about the JFK assassination, something which would help put the other clues into perspective and lead to previously unseen relationships in the mosaic of the Kennedy assassination.

If that is the case, then perhaps the whole thing is an elaborate hoax. If so, no such hoax originated with me or others whose research contributed to these findings. It cannot as yet be conclusively ruled out, though, that such a hoax originated with the car’s owner or someone who knew him. Those of us who have made these findings, with the exception of those wishing anonymity, are willing to verify the truthfulness of all statements we have made.

Maybe this is just an amazing coincidence. Whether real, coincidence, or hoax, the evidence of the UT Rambler is similar to and predates the evidence of Ricky White, which was first made public in August 1990, concerning his father Roscoe White’s role in the assassination. By the time White’s story broke in the August 5, 1990 Austin American-Statesman, I had already discovered the Rambler, the magazines, and the first of the missing pages. In fact it was the similarities between the story of the Rambler and the story of Roscoe White — the idea of leaving artifacts, clues, and documents where they could be found — that led to my curosity to start the first hard research into the Rambler in November 1990.

In the search for truth about the Kennedy assassination, rife as it is with disinformation in the accepted areas of learning, we cannot be blinded to the possibility that the truth can still be found or that it may be in some rather unorthodox places. I understand the damage that continues to be done by those who introduce red herrings, intentionally or not, into the investigation of President Kennedy’s murder.

As a group, those of us who have been investigating this Rambler decided in January 1993 that the public release of our findings would help in the search for the truth more than hurt it. After nearly four years of justifiable caution, we felt that at least some of what we had found pointed in the direction of what had actually happened to President Kennedy. In the months that followed, leading up to the presentation of our paper (at the Second Research Conference of The Third Decade in June 1993) and after, that decision was reinforced by subsequent findings. Whether real, coincidence, or hoax, the Rambler has led to a new look at those with well-known roles in the story of the assassination like Marina Oswald’s friend Ruth Paine; former CIA director Allen Dulles; organized crime figure Eugene Hale Brading: former president Lyndon Johnson; and Oswald’s CIA friend George de Mohrenschildt. It has led to a new look at those with lesser known roles like CIA and Mafia associate John Martino; former LBJ aide Howard Burris; Dallas oilman D. Harold Byrd; former spies Mary Bancroft and Edward G. Lansdale; former presidents George Bush, Richard Nixon; and former LBJ advisor Walt Rostow. And it has led to a first look at those with as yet unknown possible roles, like former UT president Harry Huntt Ransom; the car’s Late owner, UT Spanish professor George Gordon Wing; and the man he bought at from on April 26, 1963, Cecil Bernard Smith.

To quote Dr. Wing himself, from an article he wrote in 1962, in which he examines, “...a brilliant analysis [by Carlos Fuentes] of Moby Dick in terms of its profound meanings...”

...Fuentes gives us a Melville who is not only a subverter of the established order but also a prophet whose prognostications gain validity in our own time. Melville could not accept the idea of the United States held by his fellow countrymen — God’s chosen people, a nation that had never experienced defeat and felt itself heir to the future. Melville had a vision, Fuentes says, of the excesses to which all of these certainties could lead: to the imposition of false ends and private fetishes; to the sacrifice of the collective good on the alter of an abstract freedom of the individual, to the simplistic division of history into a Manichean struggle between the good — the United States — and the evil — those who oppose the United States, to manifest destiny, to “the lonely crowd,” inorganic atomism; to the confusion between private opinion and general truth; to the radical lack of comprehension of the truth of others whenever it does not correspond to the particular vision of things held by a North American: as a consequence, the truth of others is suspect and must be destroyed. Indeed, Fuentes concludes, in our time, Captain Ahab still lives, and his name is MacArthur and Dulles, Joe McCarthy and Johnson, the white whale is in Cuba, in China, in Vietnam, in Santo Domingo, in a film, in a book....20

Dr. Wing ends this same article with a statement which can be applied to other aspects of his life — a statement which may one day prove to be very revealing about what had once been viewed as his eccentricities: “In this essay, I have of necessity treated a complex subject in a somewhat fragmentary and incomplete fashion. Nevertheless, I hope to have awakened some interest in pursuing further any of the topics I have deliberately left truncated.”

(Revised and amended from the original, print-only publication, “Roger and Me,” The Assassination Chronicles, Vol. 1, Issue 2, June 1995, pp. 35-38, and Issue 3, September 1995, pp. 45-49.)

ENDNOTES:

Richard Bartholomew, “My Small World of JFK Conspiracy,” The Deep State in the Heart of Texas: The Texas Connections to the Kennedy Assassination. San Antonio, Tx: Say Something Real Press, 2018, pp. 22-23, also posted at bartholoviews.substack.com.

See “True Believers Part 2: Conspiracy-Denial Bigotry in Mass Media,” bartholoviews.substack.com.

See “The Real Conspiracy Nuts,” bartholoviews.substack.com.

David McCullough, “Why We Should Care About History,” O’Neill Memorial Lecture, National Archives, 1993.

Neal Postman with Charles Weingariner, Teaching as a Subversive Activity, (NY: Delta, 1969), p. 3.

House Select Committee on Assassinations, Vol. XII, pp. 8-9, 18. (hereafter as 12 HSCA 8-9, 18) cited in Dennis Ford. “A Conspiracy Model and a Conspirator. Predictions and Possible Refutations,” The Third Decade, (Vol. 9, No. 1, Nov. 1992), p. 25; Michael L. Kurtz, Crime of The Century, (Kaoxsille, TN: University of Tennessee Press. 1982). p. 132; Josiah Thompson, Six Seconds in Dallas, (NY: Bemard Geis, 1967, Berkeley, 1976), pp. 303-06, 404-05.

Jim Marrs, Crossfire: The Plot That Killed Kennedy, (NY: Carroll & Graf, 1989), p. 331.

Warren Commission Report pp. 160-61 (hereafter as WCR 141-61): Mark Lane, Rush to Judgment, (NY: Holt, Rinehan & Winston, 1966) pp. 173-74: Roger Crag, When They Kill a President, (unpublished manuscript, 1971), pp. 14, 18: Two Men in Dallas: John Kennedy and Roger Craig, 60 minutes, videotape narrated by Mark Lane, Alpha Productions, 1977.

Jesse E. Curry, Retired Dallas Police Chief Jesse Curry reveals his JFK Assassination File (American Poster and Pnntng, 1969), p. 72. Note: Craig never changed his Rambler story throughout his life, though apparently others did. This paper’s author accepts Craig’s own statements on the Rambler as credible and reliable. (See Two Men in Dallas, videotape.)

Kurtz, Crime of the Century, op. cit., pp. 132-33; Robert Groden with Harrison Livingstone, High Treason, (NY: Conservatory Press, 1989) p. 162. (Author's note, April 10, 2023: Like the evidence of the Rambler getaway, there is much about the bus and cab getaways that the Commission avoided. For good reason: the evidence would have established the presence of an Oswald impersonator. See “The Imitation Game,” bartholoviews.substack.com.)

Marrs, Crossfire, op. cit. pp. 332. 560.

12 HSCA 18; U.S. Congress, House. The Final Assassinations Report: Report of the Select Committee on Assassinations, U.S. House of Representatives, (NY: Bantam, 1979), p. 56; DeLloyd J. Guth and David R. Wrone, The Assassination of John F. Kennedy: A Comprehensive Historical and Legal Bibliography, 1963-1979 (Westport, CT, Greenwood, 1980), p. xxxiv.

The car’s current whereabouts is known to its researchers but will not be disclosed publicly in order to protect the car from potential vandals, thieves, and publicity seekers. (Author's note, 4/6/2023: I first revealed the car’s whereabouts and fate in my 2018 book. See the video, “Rambler Search,” first shown publicly at the November 2018 Dallas assassination conference, also posted at bartholoviews.substack.com)

https://bartholoviews.substack.com/p/rambler-search-video-7f7?r=1mvvcn

See “The Mystery of the Professor’s Door”

In Dick Russell’s book, The Man Who Knew Too Much (Carroll & Graf Publishers, first edition: 1992, revised: 2003), many names, places, dates, events, and themes are identical to the same information that reoccurs throughout missing pages in all of the mutilated books, including the Odio incident; false stories planted about Oswald in Mexico City and their coverup by CIA; Oswald’s leafleting in New Orleans; the raid on the Lake Pontchartrain camp; John Martino; Loran Eugene Hall; Rolando Cubela and the AM/LASH plot; Manuel Artime; Carlos Bringuier; Santos Trafficante; Little Havana, Miami; JFK’s secret negotiations with Castro; September 1963; Alpha 66; and the Cuban Freedom Committee.

Dennis Ford, “A Conspiracy Model and a Conspirator: Predictions and Possible Refutations,” The Third Decade, (Vol. 9, No. 1, Nov. 1992), p. 28.

See "The Lies of Texas," bartholoviews.substack.com

As attributed to the character Sherlock Holmes in the novel, The Hound of the Baskervilles, by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. (Orlando Park, The Sherlock Holmes Encyclopedia, Secaucus, NJ: Citadel Press, 1981), p. 84.

Carr described it as a “1961 or 1962 Grey Rambler Station Wagon ... which had Texas license....” Craig described it as light-green and wrote in 1971, “I said the license plates on the Rambler were not the same color as Texas plates. The Warren Commission: Omitted the not — omitted but one word, an important one, so that it appeared that the license plates were the same color as Texas plates.” [emphasis added] In a cover-up, this matter would be a prime target for obfuscation. Therefore, the consistencies in the descriptions of the car — that it was a light color, a Rambler station wagon, driven by a man with a dark complexion, and a white male identical to Oswald entered it — carry the greater weight as evidence. (See Thompson, Six Seconds in Dallas, op. cit., pp. 303-06, 404-05.)

George Gordon Wing, “Some Remarks on the Literary Criticism of Carlos Fuentes,” Rob Brody with Charles Rossman, eds., Carlos Fuentes: A Critical View, (Austin, TX: The University of Texas Press, 1982), pp. 210, 211.